Wearable motion detectors identify motor deficits

A wristwatch-like motion-tracking device can detect movement problems in children whose impairments may be overlooked by doctors and parents, according to a new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The findings could help identify children with subtle motor impairments so they can be treated before the limitations develop into potentially significant and intractable disabilities.

“I had a teenager come into my clinic because he was trying on gloves at a sporting-goods store, and the store owner noticed he was struggling to put his baseball glove on,” said senior author Nico Dosenbach, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology who sees patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “They thought he’d hurt his elbow playing baseball. But it turned out he’d had a massive stroke as an infant that damaged the motor parts of his brain, and no one had ever noticed until the store owner said something. I sent him to therapy, but he had only partial recovery. Perhaps if we’d sent him to therapy when he was a toddler instead of a teenager, it might have made a bigger difference.”

As many as 1 in 1,600 babies suffers a stroke during or around the time of birth. People are more likely to experience a stroke in the first week after birth than during any other single week of life. Such a stroke can cause a child to lose some control over one side of his or her body, but the impairment may not be noticed until years later, when the child struggles with tasks such as getting dressed, carrying bulky objects or opening a door with one hand while holding something in the other.

“Handedness doesn’t really emerge until around age 3, so if you have an infant or toddler favoring one hand, that’s not normal,” said occupational therapist and graduate student Catherine Hoyt, OTD, the paper’s first author. “But not everyone knows that, so parents might not think to mention it to the pediatrician, and doctors aren’t likely to pick up on something that subtle in a 15-minute checkup. I was looking for a way to affordably and efficiently screen for motor deficits so we can pick up on children who would otherwise be missed and get them into therapy early.”

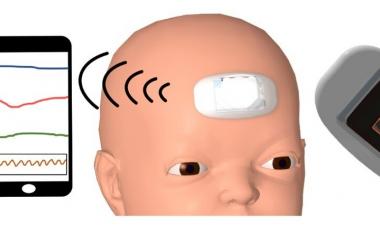

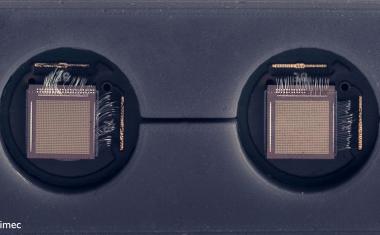

Hoyt and Dosenbach used motion-tracking devices known as accelerometers to measure how much children use each arm in their daily lives. They recruited 185 kids between 2 months old and age 17 to wear a tracker on each wrist for four days, including while sleeping, bathing or playing sports. Of the participants, 29 had been diagnosed with motor impairments, and 156 had no motor or other neurological problems.

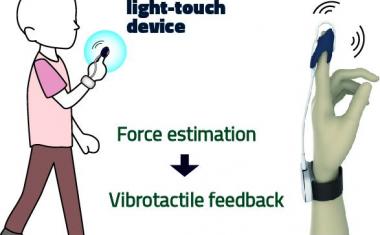

The researchers wrote an algorithm to analyze the data from the motion trackers, taking into account how often and how forcefully the children moved each arm, and how many of the movements involved both arms or just one. They found that typically developing children under age 3 used both arms equally. After age 3, the ratio shifted in typically developing children, but only slightly; right-handed children used their left arms about 95 percent as much as they used their right arms, and vice versa for left-handed children. In children with motor impairments, the ratio was significantly more lopsided.

“Many of the children with impairments used one arm only 60 to 80 percent as much as the other, which is really abnormal,” said Dosenbach, who is also an assistant professor of occupational therapy and of pediatrics. “Even that level of impairment is not always easy for a pediatrician to detect, because children often behave totally differently in the doctor’s office than they do normally.”

Clinicians sometimes rely on brain scans to identify brain damage and determine whether a child needs intensive therapy. But the size of the injury does not always reflect the true level of disability, the researchers said. “You can have a small brain injury that results in a large deficit or a large brain injury that results in a minor deficit,” Hoyt said. “By monitoring how children are actually using their arms, instead of measuring the size of the injury, we potentially could target resources to the children who could benefit the most.”

我们的目标是有一天加入运动跟踪into routine childhood checkups to identify children with motor impairments while their brains are still adaptable enough to respond well to therapy. The motion trackers used in this study are reusable and cost under $250 each, making them affordable enough for routine screening.

“I’d like to see the day when you take your 1-year-old in for a well-child visit and the pediatrician does the regular checkup, plus straps an accelerometer onto each of the baby’s wrists,” Dosenbach said. “Then, four days later, you take them off, stick them in an envelope, and send them back to the doctor, who downloads the data and runs an analysis that says, ‘This kid’s fine,’ or ‘Oh, no, there’s an abnormality. Follow up.’ That could really help us find some of the kids who are being missed.”

Source:华盛顿大学医学院的圣罗uis